In “Advanced Readings in D&D,” Tor.com writers Tim Callahan and Mordicai Knode take a look at Gary Gygax’s favorite authors and reread one per week, in an effort to explore the origins of Dungeons & Dragons and see which of these sometimes-famous, sometimes-obscure authors are worth rereading today. Sometimes the posts will be conversations, while other times they will be solo reflections, but one thing is guaranteed: Appendix N will be written about, along with dungeons, and maybe dragons, and probably wizards, and sometimes robots, and, if you’re up for it, even more. Tim is on his own this week with a look at the lesser-known novel The Face in the Frost, by John Bellairs.

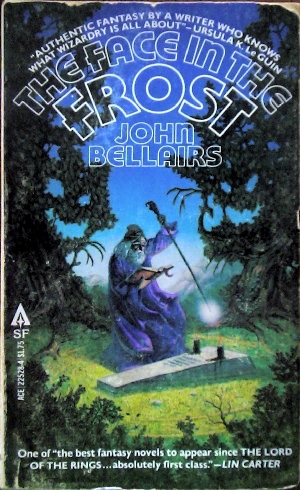

This is one of the novels Gary Gygax specifically mentioned by name, and its greatest claim to close-to-fame is that Lin Carter named it one of the three “best fantasy novels to appear since The Lord of the Rings” in his detailed survey of fantasy fiction called Imaginary Worlds.

That Lin Carter endorsement shows up on the back cover of the 1978 Ace edition and on The Face in the Frost’s Wikipedia page, so it must be important.

But if I can take a detour here for a minute—and why can’t I? It’s not like Mordicai is around to stop me this week!—then I think it’s worth mentioning that Imaginary Worlds, in addition to its ringing endorsement for the Bellairs novel, has plenty to recommend it to the Appendix N fans among us. Imaginary Worlds is something akin to a 1973 paperback version of Advanced Readings in Dungeons & Dragons written by an unabashed fantasy enthusiast who also happened to be a pretty good fantasy author himself. And it came out the year before Dave Arneson and Gary Gygax released the first iteration of D&D. But Lin Carter’s non-fiction tour through fictional fantasy ends up providing some fascinating context for many of the writers and works that would later appear in Gygax’s Appendix N. Plus, it gives some insight into how those writers and works were perceived in the early 1970s, when D&D was gestating. I wouldn’t go so far as to say that Imaginary Worlds is some kind of secret decoder ring for Appendix N readers, but it is definitely worth your time if you want to see (a) some sense of how these authors related to one another historically or (b) how much Lin Carter can gush about his favorites and provide passive aggressive dismissals of his least favorites. Both aspects make it worth a look.

Back to The Face in the Frost! That’s why we’re here! John Bellairs wrote it, and it’s full of wizards!

Other than the Jack Vance books, this is probably the most wizardy of all the Appendix N volumes. I certainly can’t think of another that’s as magic-centric. The story of the story goes like this: Bellairs—who would go on to write childen’s fantasy books illustrated by Edward Gorey—found himself in England, read The Lord of the Rings while he was there, and wanted to play around in the genre, specicially with a Gandalf-like character because he found Tolkien’s Gandalf to be relatively flat. So if you approach The Face in the Frost as an attempt at writing a more fully-realized wizard, you’ll be in the right frame of mind. And if you approach the novel as an attempt to write a wizard buddy comedy with the looming threat of another, mostly unseen, wizard, then you’re really on the right track.

This Bellairs novel is like Gandalf and Gandalf teaming up to fight an invisible Gandalf. Sort of.

The two wizarding buddies are named Prospero and Roger Bacon.

Seriously.

You probably know Prospero from William Shakespeare’s The Tempest, which you haven’t read unless someone assigned it to you at some point or you are a wonderfully-amazing person who loves Shakespeare as much or more than I do. And you may know Roger Bacon as a 13th century philosopher/scientist/Franciscan friar. But Bellairs isn’t using those historical and/or literary characters as his protagonists. He’s just stealing their names and letting you know he doesn’t take all this stuff too seriously. The Face in the Frost is a comedy, mostly, with some scary stuff that becomes increasingly weird as the story progresses. The plot kind of falls apart in the final third of the novel, but the book isn’t plot-driven anyway. It’s about the characters, and a few entertaining sequences, and some banter and some narrative flourishes and a sense of lets-have-fun-writing-about-wizards. It’s not quite Terry Pratchett silliness, but it’s closer to that than to J. R. R. Tolkien. And it’s quite entertaining on a scene-by-scene basis, like a sitcom with a couple of great actors in the lead roles.

Here’s a glimpse. In the first chapter we meet Prospero, who is using his magic mirror to see into the future and/or alternate reality of 1943 where he watches the Chicago Cubs play the New York Giants. After some scenes of puttering around the old wizard workshop, the doorbell rings, and as he opens his front door, he sees a shadowy figure:

As Prospero watched, the figure raised a threatening arm and spoke in a deep voice:

“Kill them all!”

At this Prospero did a strange thing. He began to smile. His long wrinkled face, which had been set in a tense frown, was now creased by a delighted grin.

“Kill who all?” he asked in an amused voice.

“All those blasted, pesty, nitty insects!” the figure roared.

That’s the introduction of Roger Baco,n and indicates the tone for most of the novel. Not quite parody, but playing with parodic elements and using humor to undermine the self-seriousness of the post-Tolkien fantasy genre. Bellairs pulls it off most of the time, and he makes the characters interesting enough that we care about their interactions even if some of the jokes don’t quite land. And then he does this other thing—something I’ve already alluded to—by pitting his buddy wizards against an unseen threat. It’s a powerful technique to drive the characters into action while not getting in their way by cutting to scenes of the bad buy scheming or wringing his hands. It’s kind of like Jaws, if the shark were an incorporeal evil wizard who could make things very cold and uncomfortable. That might not seem scary, but would you want to be haunted by a face…in the frost? I think not!

Anyway, that unseen threat is a former colleague of Prospero who goes by the name Melichus. Bellairs avoids having either of his characters refer to the bad guy as “Mel,” but if this were actually a D&D game, that would be the first thing the players start to call him. So I’ll call him Mel, out of respect for the game. And old Mel wants a shiny crystal ball thing that doesn’t really matter, and the plot gets increasingly less interesting as Mel draws Prospero and Roger Bacon toward the climax of the story.

But Bellairs does give us a really cool sequence where Prospero tries to thwart an invading army by destroying a stone bridge with his magic. Only, he realizes that he has no idea how to destroy a stone bridge, and he tries to use some Tarot cards and some chanting and nothing seems to work until he unleashes a fury of cards and magical commands and, well, it gets messy.

That’s surely the kind of stuff that influenced Gygax and earned The Face in the Frost a place on the hallowed shelves of Appendix N. The magic is messy in this book. It often doesn’t work, or doesn’t work as intended, and even when it does work, it’s not the sort of magic that’s super-powerful wizard laser beams or massive fireballs. It’s cantrip-type stuff. Enchanted mirrors. Little magical trinkets. Making notes and drawings in books. Trying to find the card and the right word that makes the stone bridge go boom.

It won’t change your life, or the way you play your favorite role-playing game, but for a diversion into the slightly-wacky, slightly-ominous, slightly-amusing world of wizard pals and ice cold curses, The Face in the Frost will serve you better than most. And unlike Shakespeare’s Prospero, this guy doesn’t quit at the end. So if you were writing a sequel to Lin Carter’s Imaginary Worlds, in your fannish enthusiasm you might say…John Bellairs: better than Shakespeare.

Tim Callahan usually writes about comics and Mordicai Knode usually writes about games. They both play a lot of Dungeons & Dragons.